Roohealthcare.com – A Pectoralis Major Transfer is a reliable surgical option for patients with anterosuperior rotator cuff injury. The technique is known to significantly improve pain and function. However, the procedure does have some limitations. A patient must be evaluated for appropriateness. It is not recommended for everyone. This article discusses some common complications associated with Pectoralis Major Transfer and how to avoid them. The information in this article is intended for individuals who have already had one or more arthroplasty procedures.

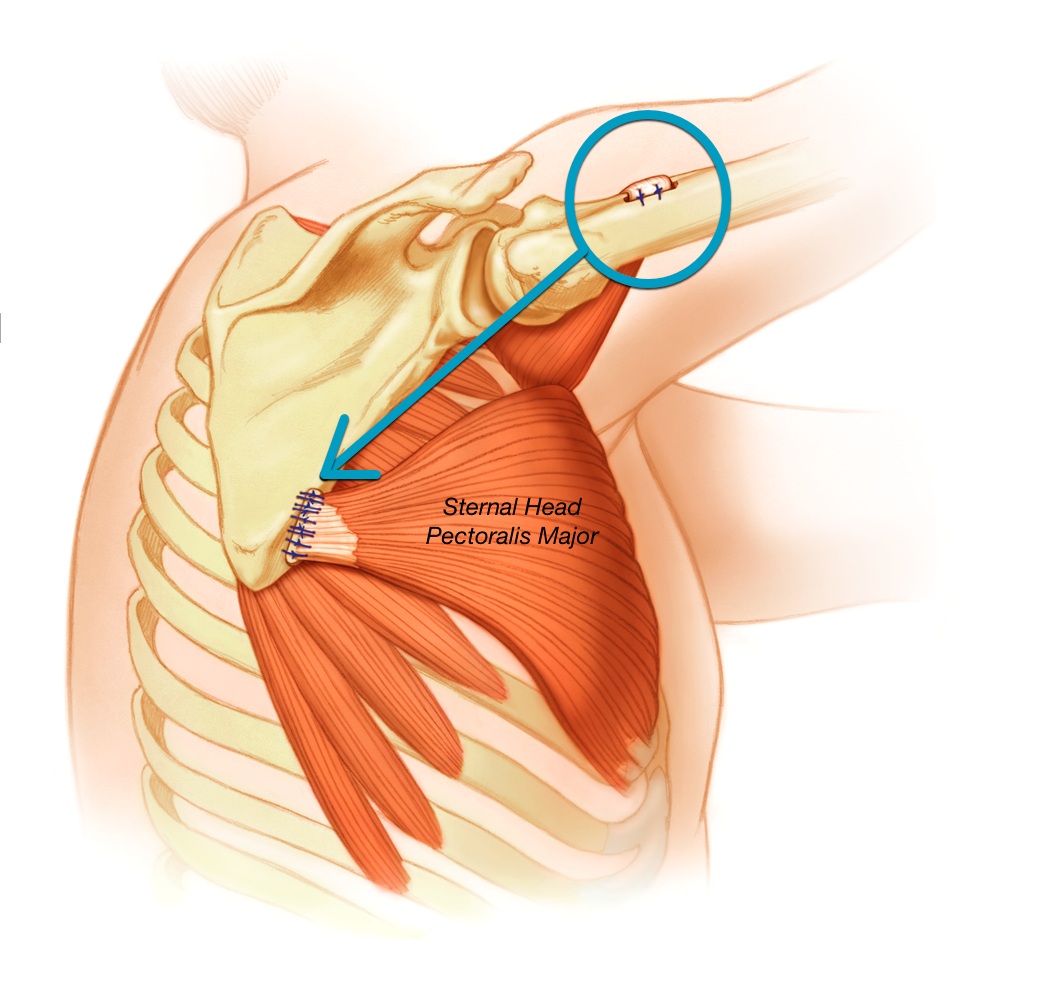

Pectoralis Major Prepared for Transfer

The pectoralis major is prepared for transfer using an autograft of the hamstring. It is performed in a modified beach chair position. A 5 to 7-cm incision is made in the chest wall. The surgeon isolates the sternal head with a Penrose drain and harvests the hamstring tendon side by side. Sutures are placed between the short and long ends of the hamstring.

A subcoracoid Pectoralis Major Transfer is a surgical technique to transfer the tendon from the lower arm to the upper arm. This procedure is particularly useful in cases where the rotator cuff has been completely torn, requiring direct tendon-to-bone reconstruction. Resch et al. performed a partial subcoracoid pectoralis major transfer in a patient with anterosuperior subluxation of the humeral head due to a massive rotator cuff tear.

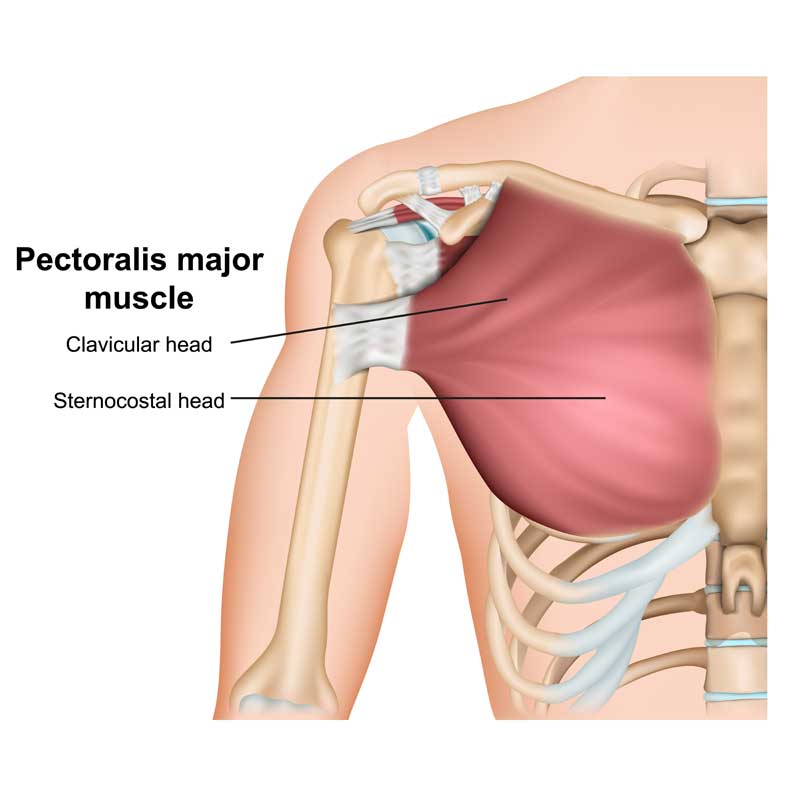

The pectoralis major muscle is divided into three parts, the clavicular head, the upper sternal head, and the lower sternal head. The clavicular head is transferred first, leaving the lower sternal head intact. The clavicular head and the upper part of the sternal head are attached laterally to the acromion and lateral clavicula.

Performing a Pectoralis Major Transfer

To perform the Pectoralis Major Transfer, the surgeon will first create wide subcutaneous flaps. This will improve visualization in the operative field. Next, the surgeon will retract the superficial clavicular head proximally and identify the most lateral insertion of the sternal head tendon. Next, he or she will digitally dissect the axillary channel. The axillary tunnel is a potentially dangerous location due to the potential for neurovascular injury.

In some cases, an irreparable rupture of the subscapularis tendon causes the shoulder to become inaccessible. A pectoralis major tendon transfer has been reported to help restore shoulder function. The outcomes of this procedure were examined in a systematic review of published articles. The authors excluded case reports, review articles, and operative techniques that did not report the outcomes. They assessed all outcomes reported by each study and used data pooling to summarize the outcomes.

The transferred tendon was then grasped using non-resorbable sutures. The musculocutaneous nerve was placed anterior to the conjoined tendon. The muscle was subsequently passed from the medial to the lateral direction. The anterior part of the tendon was protected, and the nerve was not crossed. The patient’s pain was alleviated. The Pectoralis Major Transfer has been successfully performed on a number of patients.

The Most Common Locations for the Pectoralis Major

The pectoralis major muscle originates from the medial clavicle, the sternum, and the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle. The clavicular muscle belly accounts for 60% of the muscle’s cross-section. A muscle bellies’ insertion on the humerus and greater tubercle is the most common location for the pectoralis major muscle.

Surgical recovery from Pectoralis Major Transfer can take over a year, depending on several factors. Patients should expect to undergo a passive range of motion exercises for 4 to six weeks after surgery. The active motion should be performed after this period. After a year, patients are able to return to full weight-bearing activity. Although this procedure requires a lengthy recovery, the overall outcomes are good. In some patients, the surgery has improved strength and range of motion.

A 59-year-old man presented with anterior dislocation of his right shoulder. He had an anterior-superior rotator cuff tear, but there was no evidence of a prior anterior capsulolabral injury. He underwent arthroscopic rotator cuff repair and postoperative rehabilitation. At 10 months after surgery, he experienced another anterior shoulder dislocation. Fortunately, a diagnostic arthroscopy revealed a retear of the anterior-superior rotator cuff and involvement of the Hill-Sachs lesion.